GUIDE TO LIFE

III Productive Living

IV Autobiography

V Beauty

VI Art-Making

- Inner Voices (Worry)

- Familiarisation with Strange Spaces 1

- Familiarisation with Strange Spaces 2

- Sometimes I get Tired of Questioning my Motivations

Three works, Anthony Reynolds Gallery, London, 2005

| Chapter VI | Art-Making |

| Part B | Strategies |

| 3(a-c) | Repeating Works: New Work (Guide To Life VI(A).2(a-d)); Documentation of Repeated Work (Guide To Life VI(A).1(a-d)); Text. |

| Chapter VI | Art-Making |

| Part A | Techniques |

| 3(a-c) | Commissioned Work 2: Floor Work; Drawing; Video; Text. |

| Chapter IV | Autobiography |

| Part C | Experiencing The World |

| 6. | Sometimes I Get Tired of

Questioning My Motivations: Floor Work; Drawing; Video; Text. |

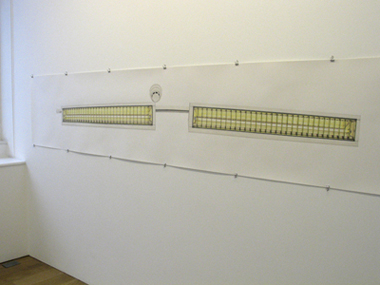

On the wall on the left is the documentation of the repeated work "Commissioned Works" and a plastic case containing copies of the three texts printed as a booklet for visitors to take away.

Floor work: Circa 18 m2, Inkjet print on Forex.

A computer drawing showing a central perspective view looking up the stairs was printed onto 40 x 40 cm Forex boards, which were laid together to form a floor ornament.

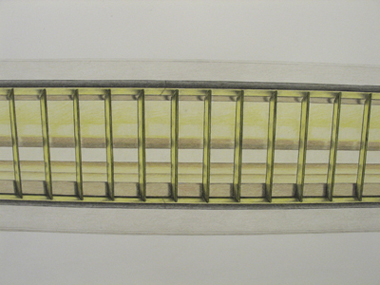

Drawing: 600 x 50 cm, coloured pencil on paper.

The drawing shows a 1:1 representation of the fluorescent light on the ceiling above.

The looped video shows a slow-motion pan along the join between the floor and wall/floor and counter behind the gallery desk.

GUIDE TO LIFE VI(B).3(c): Repeating Works (Text)

Introduction

Guide To Life, although conceived to communicate specific conceptual or expressive ideas, is above all an artistic strategy that was formed in response to my particular, personal artistic needs. Guide To Life offers me a feeling of security - or rather an illusion of security - within the otherwise almost unbearable arbitrariness and self-indulgence of an artistic practice, which in turn takes place within the otherwise almost unbearable pointlessness of life itself.

The chapter Art-Making in Guide To Life looks at technical, conceptual and strategic aspects of the process of making art. It covers issues that are neither exclusively to do with my personal experience of being an artist (covered in Chapter IV: Autobiography) nor exclusively to do with issues of aesthetics (covered in Chapter V: Beauty).

Titles within Guide To Life are always strategic in that the title can be used to assert something about the work, to which the work can then respond.

Repeating Works

Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works is an investigation of what happens when you repeat a work. I wanted to do this work because I constantly worry about becoming repetitive in my work. Sometimes I find myself fearing my future as an artist. I worry that all I have to look forward to is the drying-up of my passion, the loss of my ideals, the decline of my physical and mental capabilities and the shrinking of my sphere of interests until I reach the artistic death of making the same work over and over again. This vision is symptomatic of a fundamental lack of acceptance of inevitable, and therefore non-tragic, human limitations; but since the repetition of works plays such a central part in this vision, it is worth investigating if I am right in viewing it so negatively. It could be that repetition is the only possible way to deeply investigate things. Maybe when I try to resist repeating myself, I am refusing to truly engage with the work that I make. I never have to accept anything I do as my real work, as a definitive statement about my interests and capabilities, because I am always hedging my bets by imagining the new, different work that I will make next.

The work Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works is an attempt to come to terms with something that is unavoidable. I suspect that my view of a future in which I constantly produce the same work over and over again is realistic, as, when I am honest with myself, it’s not really a question of what might happen in the future, but something that is already happening. I may try to deny it, but I do know that I’m limited in the work that I am capable of producing. I am hoping that by making a deliberate, rather than accidental, decision to repeat myself I will force myself to accept this reality. It is, after all, ultimately depressing and unproductive to continue to hold onto an ideal that can’t be achieved.

The work Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works is a repeat of the work Guide To Life VI(A).1(a-d): Commissioned Works. In repeating this work I not only produce the work Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works but I inevitably also produce the work Guide To Life VI(A).2(a-d): Commissioned Works 2 as when I repeat the work Guide To Life VI(A).1(a-d): Commissioned Works I can’t avoid re-engaging with the issues to do with commissioned works that I first encountered in that work.

Guide To Life VI(A).2(d): Commissioned Works 2 (Text)

This text is a slightly altered version of the text that was part of the work Guide To Life VI(A).1(a-d): Commissioned Works.

Commissioned Works are works produced as the result of a commission, i.e. they are motivated by forces external to the artist. Commissioned works often respond to the specific place or situation where they are exhibited (“exhibit” in the sense of making a work available to an audience). The opposite of commissioned works are works produced in the studio out of the artist’s sense of internal necessity, and which are intended for exhibition in white cubes (“white cube” being a space that is clearly placed within, and follows the accepted exhibition practices of, the art world).

I started thinking about commissioned works because of what happened, or rather didn’t happen, in my career last year: I had no opportunities to show my work in the sense of being given the use of a space in which to install work, but was instead invited to produce an evening event in an artist-run bar, an evening event in a gallery space within an existing exhibition and a public art work for a school. Artists are frequently expected to fulfil assignments in this way. Although our work should only ever be motivated by our internal necessity, we often find ourselves producing work in response to external demands. This puts us in the contradictory position of making a work to fulfil a purpose despite knowing that art, as soon as it becomes functional, ceases to be art. This statement can of course be disputed but only in reference to a historical context where art had the function of representation. The art content of a historical work, however, is always distinct from the functional content: it is never a recognition of how beautifully the representational or political needs of the commissioner were fulfilled which transports us into breathless wonder; and the artists themselves fulfilled the functions that were demanded of them not out of conceptual conviction but because that was the condition for being an artist.

Knowing all this, I was at first in a dilemma as to whether I should even accept these commissions, but I couldn’t in the end bring myself to refuse. Maybe I had a dream that I too could make works that would rise above the context and transcend the imposed functionality. Or maybe I just wanted to enjoy the reprieve that a commission brings from the otherwise constant struggle for self-motivation. Or maybe it was simply professional realism as these were the only offers I had. When confronted with commissions I also have a tendency to lose a sense of myself as a free agent and to slide into an attitude of passively accepting my fate, as I reason that anything that I am so deeply unwilling to do and which so goes against my natural inclinations must have something vital to teach me. I think it’s a combination of my culturally unavoidable religious fatalism, which tells me that I receive exactly what I deserve and that everything happens for a reason, and my artist’s superstition which tells me that the offer that I refuse will be my last.

So I accepted the commissions. Before I started to think about specific works I could produce, however, I wanted to devise a strategy for responding to these commissions in a way which would be least disruptive for my real work: i.e. the work that I was producing in the studio out of my own internal necessity and which was conceived for exhibitions in white cubes. I hoped initially that it would be possible to simply use a work from my studio in intentional disregard of the fact that the works were intended for particular situations. In this way I could both have avoided having to break my workflow to produce something specific for the commissions and at the same time made a statement about the validity of ever adjusting work for outside demands. My need to intentionally disregard, however, showed that I felt the need to justify my disregard as a deliberate conceptual decision: which showed that I believed that I was not able, in fact, to ignore these situations. It can, of course, be argued that there are no situations that can be ignored, as even an apparently neutral white cube is firmly placed in the socio-political context of the art world; but in a white cube it is an accepted convention that we are allowed to ignore both the physical space and the context. If a work in a white cube does respond to the space or to the context of the art world, then it is not read as a strategy born of necessity, but as a freely chosen artistic decision. The spaces and situations for which I had been commissioned to produce works were not governed by this convention, however, so I had to respond to them. I could have responded with intentional disregard, but this would have been a dangerous strategy: it is very important to me that my work appears considered and meaningful, and the risk would have been too great that a conceptually based wilful ignoring could be misread as ignorant ignoring.

So I made works that responded to the particular situations and, although I was happy with them, I had a different relationship to them than to my other work. I had trouble justifying them to myself and I felt defensive about my identification with them. I couldn’t quite convince myself that they weren’t completely pointless and arbitrary as, despite the fact that I genuinely did like them and they genuinely did interest me, I couldn’t see how there could have been any internal necessity involved in responding to spaces and situations that I only responded to because I had been commissioned to do so.

I couldn’t stop thinking about these commissioned works and the issues they had raised. I kept thinking about them even after I received an offer to exhibit in Anthony Reynolds Gallery, although this was, finally, my chance to exhibit in a white cube where I could show what I was producing in my studio. I felt that it was essential for my artistic integrity to understand the reason for my continued ambivalence towards the commissioned works, before I turned my back on them in favour of my “real” work. I had become suspicious about how I saw myself as an artist and, in particular, the extent to which my self-image had become dependent on how I was seen by the outside world. Before 2004 I had had a relatively long streak of good luck where I had had enough exhibitions in white cubes, but last year, feeling that my “real” work was being ignored, I was genuinely taken aback by how lost I felt. I had always prided myself on knowing that, however difficult I may sometimes find it, I alone am responsible for upholding my sense of myself as an artist and as a participant in a wider art discourse. My level of insecurity last year, however, shocked me into realising just how far I had allowed myself to be seduced into giving up this responsibility to others. The problem of creating and maintaining a self-defined artistic identity is, of course, a wider subject than can be dealt with here; what is relevant here is the particular way in which our attempts to self-identify can be jeopardized by commissioned works. When we are commissioned to produce a work, we are chosen because of our particular professional image as an artist: in other words because of a set of expectations as to how we will respond. Since commissioned work is a balancing act between our needs and the needs of the commissioner, it requires deliberate, sustained effort to remain true to our internal necessity. Faced with this it can be very tempting to renounce the struggle and to simply follow what is expected of us; particularly as we soon recognise that nothing more is needed for our professional survival. This can set a process in motion which results in a complete loss of contact with our self-defined identity and with the work that our internal necessity would have otherwise driven us to make, leaving us ultimately helpless to do anything but continue to follow expectations, to emptily act out our professional image. It is important to recognise the difference here between commissioned work and an exhibition in a white cube, as although we are also invited to exhibit in a white cube because of our professional image the conventions there, which include an assertion of the creative sovereignty of the artist, can actually strengthen us in resisting what is expected of us.

I decided that the best way of resolving my questions about commissioned works would be actively to go on the offensive: by deliberately recreating the conditions that had given rise to them. So I deliberately gave myself the commission of making a work for Anthony Reynolds Gallery. I wanted to find out if it would be possible to make an internally necessary work, a work that would feel like it belonged with my other work, in response to a commission. Using a traditional exhibition in a white cube to explore these questions might seem paradoxical, but it would in fact only be possible here. If this was a real commission - rather than self-imposed - and if the exhibition context wasn’t a white cube, then I would be forced to respond to the situation: it is conceptually important to me that my work feels meaningful; and to be meaningful the work would have to respond to the situation. In a white cube like a commercial gallery however, there is no conceptual necessity to respond, so the success of the work doesn’t depend on how successfully it responds to the commission but on how successfully it can be turned into a vehicle for answering my questions.

So I walked through the gallery and I deliberately chose a situation that I would otherwise feel resentfully forced in to. I deliberately sought out those absurd moments which always seem to be part of making commissioned works - moments like looking at the lights on the ceiling for so long that all of a sudden the different shades of yellow start to look beautiful. I relived the feelings that I had last year. I felt again the feeling of impending despair that comes in those moments where I find myself walking through a space (a building, a city) or thinking about a situation and wondering what I can respond to and where I can place a work. I felt again the tragedy of being forced into a situation that has so little to do with why I think I’m an artist. However naïve it may seem, I do genuinely believe that art is something uniquely important, intrinsically beautiful and a true source of transcendent happiness, and although holding on to these beliefs is certainly always a struggle, making commissioned works represents a particularly bitter and unmerciful confrontation with the reality of the artist as service provider.

I realise, of course, that my beliefs are nothing more than reactionary romanticism. I expect that I will eventually recognise that there is nothing tragic about being an artist with a job to do and that there is no shame in just trying to make the world a bit prettier. I’ll probably discover that commissioned works are actually more exciting than my other work, because, not being driven by my internal necessity, they can present me with questions that otherwise I could never have asked. Or maybe it’s precisely here that I will find the transcendence that I seek: I will deliberately renounce the romanticism of my beliefs and in so doing will positively embrace my human limitations; and in this instant I will probably feel a joy that has nothing to do with a therapeutic self-acceptance but is an authentic transcendent experience.

Guide To Life IV(C).6(d): Sometimes I Get Tired of Questioning My Motivations (Text)

The work Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works is an important work for me. Not only is the issue of repetitiveness something that I worry about and therefore something that needs to be investigated, but also - in the creation through this work of the work Guide To Life VI(A).2(d): Commissioned Works 2 - I have the added bonus of being able to re-explore and deepen my understanding of the issues surrounding commissioned works.

That being said, however, I have to admit that I’m not really sure why I’m doing the work. I notice that while I’m both emotionally and aesthetically satisfied by the process of physically making the work, every time I start to try and think about my motivations, I find myself refusing to cooperate.

Sometimes I just really want to make a particular work. I can’t convince myself that this desire is fed by my internal necessity, as there’s not a feeling of being driven to do something because it seems to be necessary or right, but just a feeling of wanting to do something. Of course, ultimately there may be no difference between the two. Maybe when I feel as if I am being driven by my internal necessity rather than by desire it is only because I have been more successful in inventing reasons to convince myself that I know what I’m doing. I’m not sure.

I don’t feel comfortable when I make a work just because I want to. I want to feel like I know why I’m doing something. I keep thinking about the work Guide To Life VI(B).3(a-c): Repeating Works, and I ask myself whether it really is important to me or if it really does explore important issues, and I ask myself what my real motivation for making the work could be, but as soon as I ask myself these questions, I realise that I’m not really interested in the answers. It’s not that the questions themselves are uninteresting, but that when I think about my experience of making the work, it all feels completely beside the point.